Data is an important part of telling the stories of what we do. To inform that story, we need to understand who we are working with (also referred to as demographics) and describe these groups. We then need to be able to show that what we are doing is making a positive difference, which is about measuring changes. This requires us to have an understanding of different data sources. In this section, we will deal with how to identify relevant data, describe and discuss the data you have and support your story with evidence.

Data is an important part of telling the stories of what we do. To inform that story, we need to understand who we are working with (also referred to as demographics) and describe these groups. We then need to be able to show that what we are doing is making a positive difference, which is about measuring changes. This requires us to have an understanding of different data sources. In this section, we will deal with how to identify relevant data, describe and discuss the data you have and support your story with evidence.

Types of data

Quantitative and qualitative data

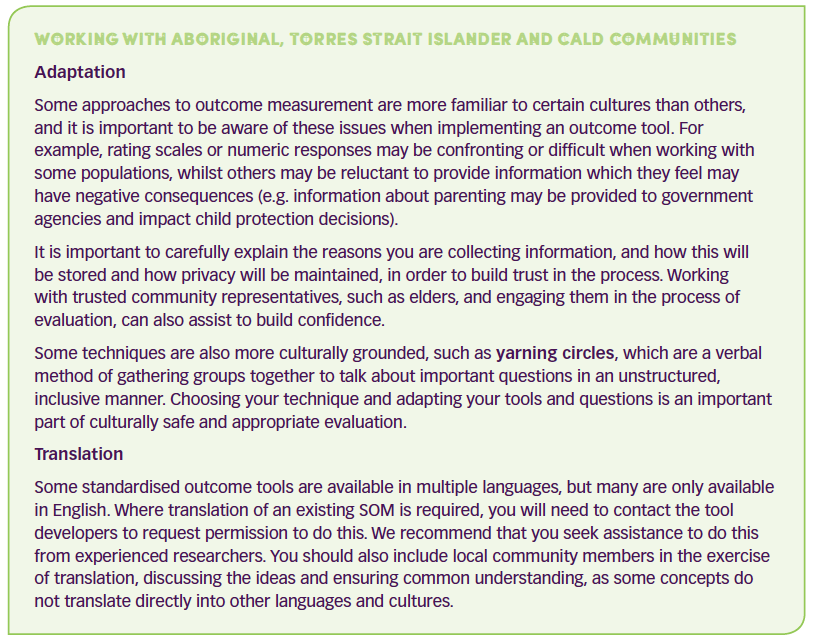

Your program may work with a range of information sources. This could be in the form of numeric responses or quantitative data (such as age or income). There may also be relevant descriptive or qualitative data, such as ethnic identify or relationship status. You can describe your population groups using this information, and some of this information can also be used as program participation criteria where applicable. For example, a program for a specific cultural group may use this information to screen who is suitable for program inclusion.

»» Qualitative questions can be used to gain an understanding of underlying reasons, opinions, and motivations. e.g., ‘what parts of our program did you find most useful?’

»» Quantitative questions are used to measure a particular aspect, behaviour or other item of interest. e.g., ‘how many times have you done X in the past week?’

Program evaluations almost always use a mix of questions. For example:

»» Using qualitative methods after a quantitative study to understand the results.

»» Using quantitative methods to test a theory that has been developed using qualitative methods.

»» Conducting qualitative and quantitative methods concurrently to question or confirm the findings from either method.

Primary and Secondary data

Another way to think of your data is in relation to what you ask yourself, and what you obtain from elsewhere, or primary and secondary data.

»» Primary data refers to the data that you capture yourself, for the purpose of answering a specific question. This may be in the form of rating scales, scores or other numeric indicators, which can provide some form of measurement or descriptive information and is referred to as quantitative data. Alternatively, qualitative data includes interviews or focus groups.

»» Secondary data refers to data captured for other purposes, such as health care usage, school records, enrolments or referral patterns. This is useful information to support and inform program evaluations, especially where specific external behaviours are targeted, such as increased school attendance or reduced police involvement, and can reduce the data collection burden for participants.

Data sources and collection methods

Family services organisations have access to a wide range of data sources. It is beneficial to use a combination of different information sources to cross check the results, such as surveys, observer ratings and existing records.

Personal interviews and focus groups provide useful information about how participants are experiencing the program. However, they can be time-consuming, do not support direct pre and post program comparisons and the analysis can be challenging.

Interviews can be structured where the same questions are asked of each participant (e.g. it might be important to make comparisons across responses in some cases), semi-structured where a researcher might wish to include certain topics in the interview, but not specific questions, or unstructured to gather in-depth information or create shared meaning or a narrative.

Focus groups are a form of qualitative research in which a group of people are asked about their perceptions, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes towards a product, service or concept.

Existing records (a form of secondary data) can save a lot of time and effort, as there is already useful information available, such as school records, health care utilisation or other measures of behaviour. However, they may not answer all the questions that you want to ask.

Observer ratings, as a complement to other methods, can be useful to conduct simple behaviour counts about behaviours of interest. This can be done using standardized rating forms or constructed forms, and it is good practice to have two observers rather than one to reduce bias and increase accuracy.

Surveys: When you have specific questions you wish to ask, you can build these into a survey instrument or tool, either paper based or through web-based programs. This enables you to include customised questions as well as use standard items (see standardised outcome measures below). You can administer surveys with electronic links for most population groups, and facilitators can have a tablet with the survey to provide this to participants during sessions if required.

However, some populations may have low technological literacy or be illiterate and will need other means to complete a survey. When designing a survey, you need to think about the questions you are asking to ensure they are well targeted and specific, and the response options you provide. Responses can range from simple to more complex rating scales, and analysis will depend on the nature of the questions you ask.

»» Dichotomous or simple yes/no questions provide the easiest answers, but minimal information: e.g., have you ever been clinically diagnosed with depression (yes/no)?

»» Multiple choice responses offer a fixed set of answers, from which participants can select one or more responses, and are good for collecting factual information. However, you may miss important information, and it can be helpful to have an open-ended ‘other’ option.

E.g. How many hours did you spend with your children in the last week?

0 hours 1-3 hours 3-6 hours 6-12 hours More than 12 hours

»» Likert (rating scales) are used to measure opinion-based questions, where participants can rate their preferences, attitudes, or subjective feelings on a scale. One benefit of using this type of scale is that many respondents are familiar with the format and will find them easy to complete. It is common to use a 5-6 point scale, with the 6th point reserved for the “don’t know” response. Smaller scales run the risk of not capturing the respondent’s choice, while larger scales can lose meaning.

E.g. I give my child a treat, reward or fun activity for behaving well.

1 = Not at all 2 = A little 3 = Quite a lot 4 = Very much

Standardised outcome measures (SOM’s) refer to existing data collection tools that have been shown as being able to consistently measure specific outcomes in different contexts. They provide a robust indicator of change where the core components of the programs are therapeutic in nature. SOM’s are also useful for measuring outcomes, as they have already undergone rigorous testing in research environments. This can enable greater confidence in the results and comparison of the results against normative data (that is data that is representative of the wider population that provides a reference point).

SOM’s need to have reliability and validity.

»» Reliability is the degree to which an assessment tool produces stable and consistent results, and there are a range of indicators of this.

»» Validity refers to how well a test measures what it is supposed to measure.

While reliability is necessary, it alone is not sufficient. For a test to be reliable, it also needs to be valid. For example, if your scale is off by 5kg, it reads your weight every day with an excess of 5kg. The scale is reliable because it consistently reports the same weight every day, but it is not valid because it adds 5kg to your true weight, so it is not a valid measure of your weight.

Well-developed SOM’s will provide information regarding the reliability and validity, as well as population norms and guidance in interpreting results. However, for small samples or exploratory studies, they can be limited in their usefulness, and you may need to ask additional questions, or use qualitative techniques to explore the outcomes more fully.

Keep in mind: altering or using partial measures can obscure the measure’s validity.

Keep in mind: altering or using partial measures can obscure the measure’s validity.